Vědecké teorie vzniku mentálního obrazu:

Pictorial theory: the mental image is depictively represented in the visual buffer

Descriptive theory: the mental image is propositionally represented by amodal descriptions

Enactive theory: the mental image is not represented directly. Instead the processes that lead to the experience of mental imagery are encoded in the respective schemata

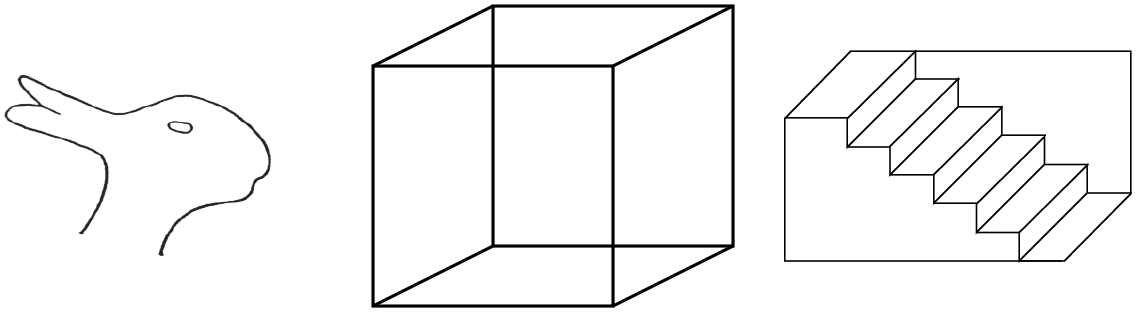

The spatio-analogical character of mental imagery refers to the fact that behavior in mental imagery is often analogical to behavior expected for an actual picture. The mental scanning effect is an example that shows this spatio-analogical character of mental imagery. There are several more examples, e.g., inspecting “smaller” parts of a mental images takes longer than inspecting “bigger” parts (for an overview of similar studies, see Kosslyn, 1980). The three theories explain this spatio-analogical character of mental imagery as follows:

Pictorial theory: The spatio-analogical character of mental imagery results from the spatio-analogical structure of the visual buffer which holds the depictive mental image. That is, the processing of the mental image is determined by the structure of the mental representation.

Descriptive theory: The spatio-analogical character results from the non-functional application of one’s tacit knowledge. That is, applying the knowledge of what perceiving the to-be-imagined entity would be like and subconsciously emulating of these properties, e.g., expected reaction time patterns.

Enactive theory: The employment of the processes of visual perception including non-mental processes such as eye movements give mental imagery the same spatio-analogical properties that the visual system has, e.g., longer attention shifts (such as saccades) take more time.

The three theories, furthermore, differ in their assumption of what mental imagery is:

Pictorial theory: mental imagery is the processing of the mental image in the visual buffer using processes of visual perception. This understanding is based on the assumption that the visual buffer is similarly used during visual perception to provide a mental representation of what is currently perceived.

Descriptive theory: mental imagery is the processing of the respective amodal descriptions which represent the mental image. These descriptions are not processed by modality-specific mechanisms such as processes of visual perception. Mental imagery is further defined by the concurrent (non-functional) application of one’s tacit knowledge about how the content of the current mental image would be perceived in visual perception. Tacit knowledge causes the characteristic behavior, e.g., reaction time patterns, of mental imagery. If descriptions are processed without the application of tacit knowledge, this would be considered general cognitive processing and not mental imagery.

Enactive theory: mental imagery arises through the employment of those schemata which are otherwise used to perceive real-world entities. It is those entities which are mentally imagined when these schemata are employed without fitting real-world stimuli. That is, the re-enactment of the perception of an entity corresponds to the mental imagination of that entity

Jako základ používám Perceptual Instantiation Theory (PIT) která je založena Enactive theory ale obashuje i prvky z pictoral a deescriptive theory.

The Perceptual Instantiation Theory

http://cosy.informatik.uni-bremen.de/si ... magery.pdf

The enactive theory emphasizes the role of the attentional and perceptual processes directed at external stimuli, e.g., the

role of eye movements, in perception and mental imagery. In contrast, the pictorial and the descriptive theory are generally not concerned with these processes and do, instead, assume mental imagery to be realized on a “higher” level. That is, the processing of mental representations by mechanisms aimed not at external entities but at the mental representation of entities.

Accordingly, the understanding of visual perception of the enactive theory differs from that of the other two theories.

Perception in the enactive theory consists of several different specialized perceptual instruments which are selectively used to retrieve specific information from the environment. In the other theories, in contrast, perception seems to be assumed as a much more generic process whose major task is providing input to the visual buffer (in the pictorial theory) or to the propositional descriptions (in the descriptive theory). The relevant processing of visual perception and mental imagery is accordingly based on these resulting mental representations.

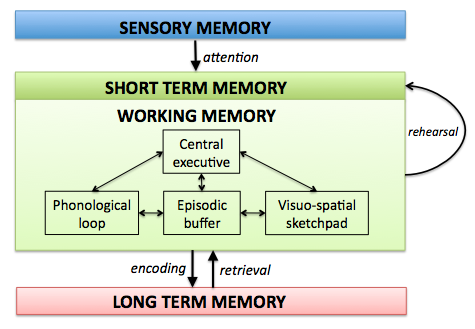

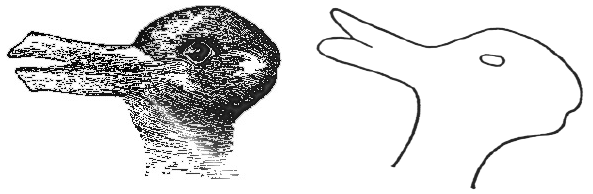

This view of visual perception means that recognition is not a comparison or pattern-matching process working on a mental representation of what is currently being perceived. But recognition is the successful application of specific perceptual actions to the external stimulus, e.g., the eye movements and their respective feedback lead to the recognition of a square. After the perceived object has been interpreted as a square, much information is discarded and an abstract conceptual description of the object remains in long-term memory. That is, if one remembers the object in question after some time, the fact that it was, for example, a red small square, remains, but many details, such as the exact size, location, orientation, or color, are often missing or have been replaced by generic information.

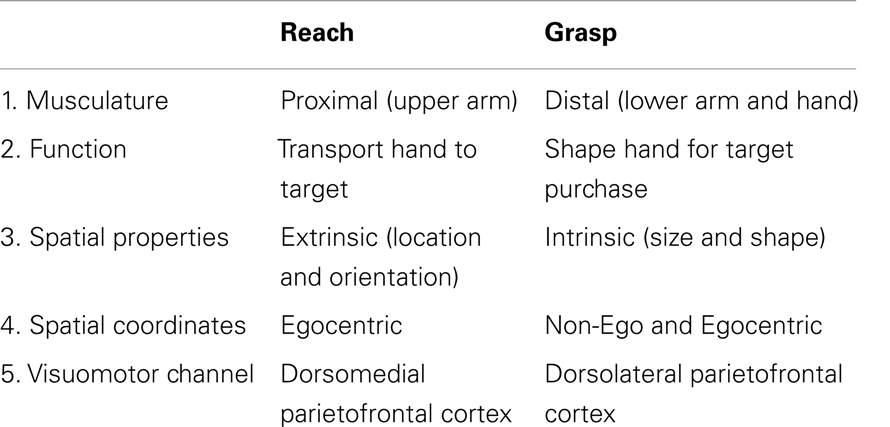

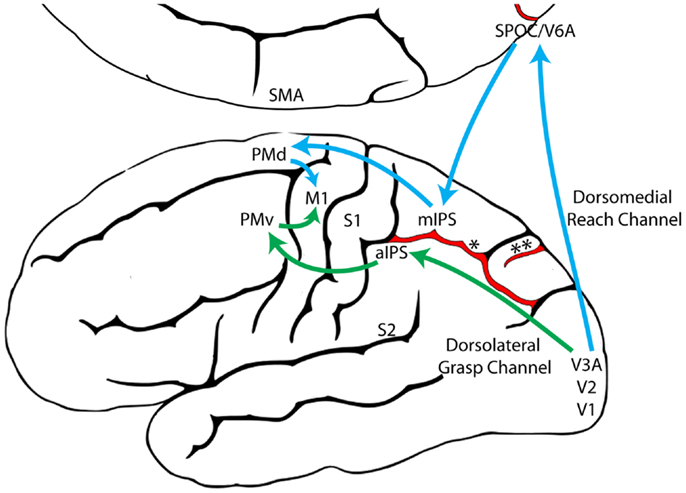

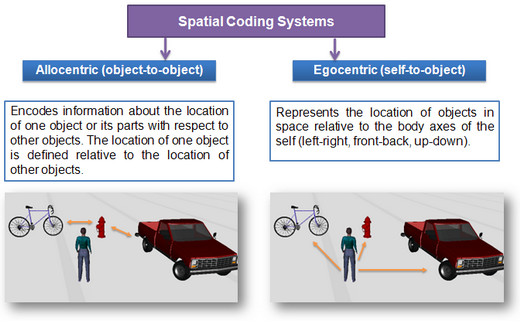

The information that has been lost by this abstraction comprises the low-level information that was made available by the perceptual actions. This includes, specifically, the coordinates of the object in an ego-centric reference frame, through which information about concrete size, orientation, depth, location, and visual features of the object can be determined. Such information is available during and shortly after the perceptual process on that level of granularity that the visual system is capable of perceiving and distinguishing. This information is referred to as perceptual information. In contrast, the abstracted conceptual memory of that object – red, small, square – could be seen as qualitative information, but will be referred to as conceptual information, or simply mental concepts.

Visuo-Spatial Long-Term Memory

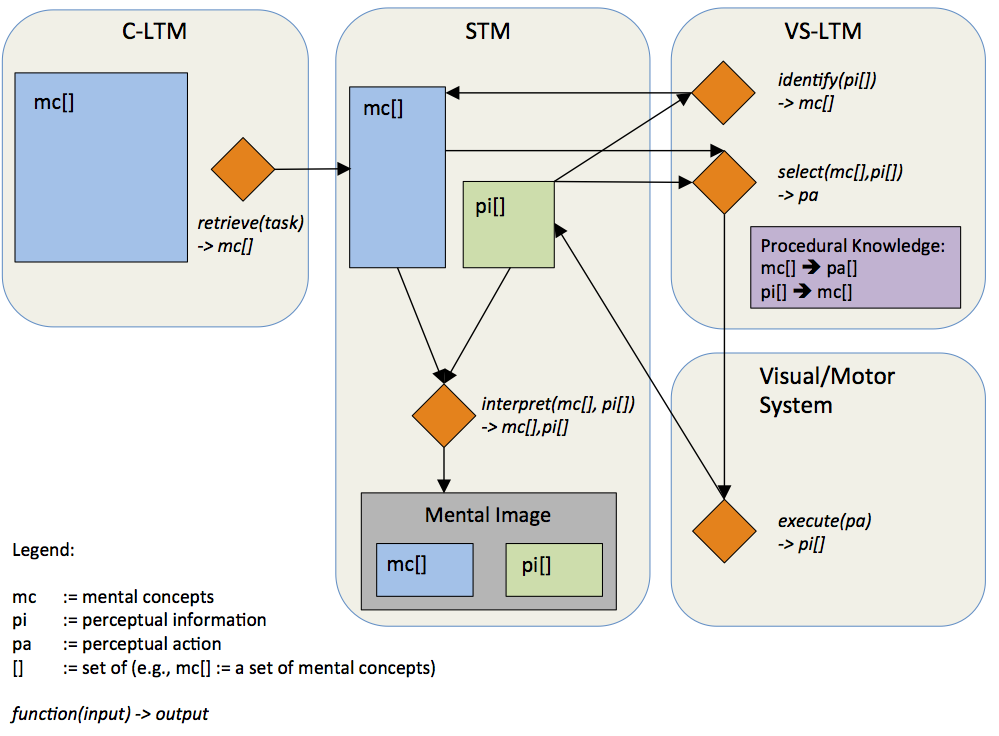

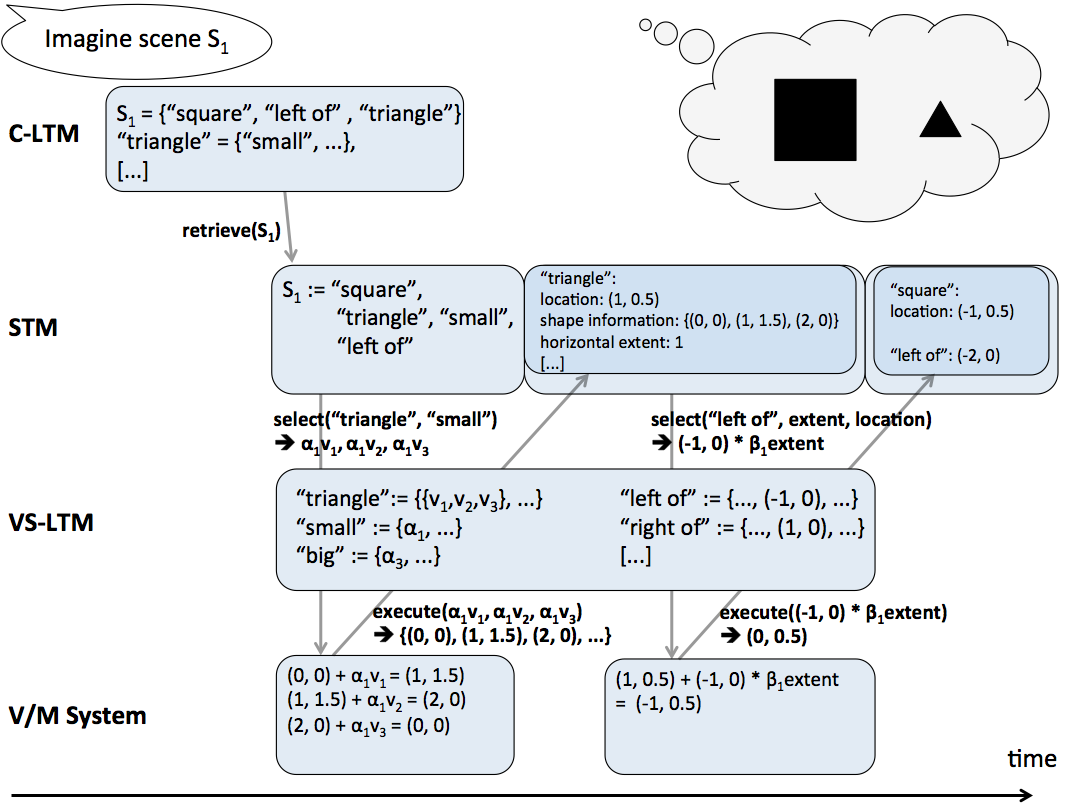

The visuo-spatial long-term memory (abbreviated VS-LTM) constitutes the procedural knowledge of how to look at the world in order to recognize entities, properties, and relations. For this purpose the VS-LTM provides two mappings: 1) a mapping of perceptual information onto mental concepts, and 2) a mapping of mental concepts onto perceptual actions. These mappings are acquired procedural knowledge and are continuously adapted.

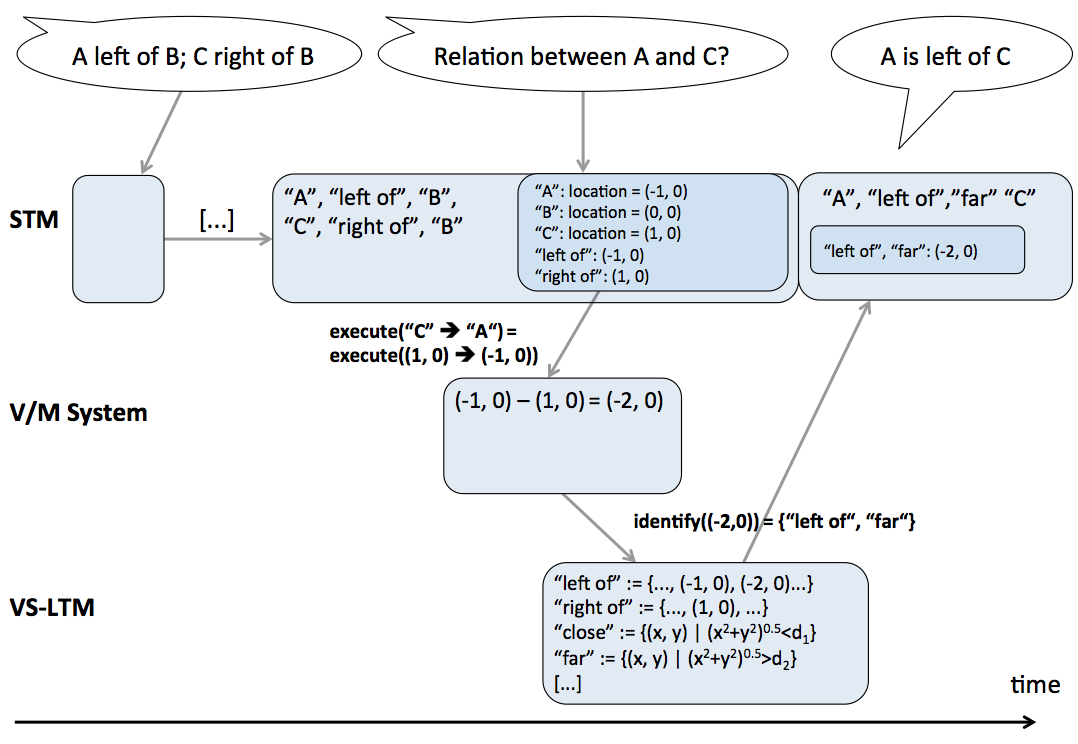

The currently identified or partially identified mental concepts and the temporarily available corresponding perceptual information determine the perceptual action that will be executed next. This step is realized by the other mapping provided by the VS-LTM: the mapping of mental concepts onto perceptual actions.

It is assumed that the strategy of choosing a perceptual action in a given situation follows the principle of maximum information gain. That is, the strategy is to choose that perceptual action which is expected to give the maximum gain of information about what the perceived object or scene is. Such strategies are considered in vision research for scene and object recognition (e.g., Schill, Umkehrer, Beinlich, Krieger, & Zetzsche, 2001). For the example of the partially identified mental concept square, i.e., the location and orientation of three edges have already been perceived, the next perceptual action would be an attention shift towards an anticipated fourth edge to gather support for the hypothesis that the object in question is indeed a square. This attention shift might be another saccade. The planning of that saccade takes into account the available perceptual information of the already known edges. That is, the to-be-attended-to fourth edge is anticipated to have a location and orientation fitting with the already known edges. The saccade is then executed towards this specific location. Given that the edge is found at the respective location, the next chosen perceptual action would retrieve the orientation and other visual features. The perceptual feedback, i.e., the location provided by the saccade and information about the orientation, lead to the full identification of the mental concept square.

The mapping of mental concepts onto perceptual actions is also a many-to-many mapping. That is, one mental concept can be identified by several different (sets of) perceptual actions and different mental concepts can be identified by employing the same perceptual actions. For example, to check for the fourth edge of a square, both an appropriate saccade and an appropriate head movement are possible. Furthermore, information about distance as well as information about direction between two given objects can be retrieved by the same perceptual action such as a saccade.

* pridat akce z koncepty

Perceptual Actions

It is an assumption of PIT that almost all perception is mediated by and thereby connected to respective perceptual actions. Examples of perceptual actions of visual perception include saccades, micro-saccades, head and body movements, adjusting the focal length of the lens as well as covert actions such as covert attention shifts.

Different types of information are retrieved using different perceptual actions. For example, information about locations and spatial relations can be retrieved by saccades, while smooth pursuit is used to track the movement of an object, and adjusting the focal length of our lenses gives information about depth.

Mental Concepts

The memory of a previously perceived scene corresponds to a conceptual description of that scene in conceptual long-term memory (C-LTM). Conceptual descriptions consist of mental concepts. Mental concepts include spatial relations (e.g., left-of, close), objects (e.g., square, house), and properties (e.g., red, big). The C-LTM comprises all mental concepts and associative links between them. The C-LTM can be understood as what is often referred to as declarative or associative memory (Anderson, 2005). The mental concepts of PIT have two important properties: 1) they are grounded symbols and 2) they incorporate input from all modalities. These two properties will be elaborated in the following.

*modou obsahovat mnohem přesnější informace

The mental concepts of PIT are grounded symbols in that they function

as hubs linking to perceptual actions.

The linked perceptual actions are those which are used for the perception of the entity that the respective mental concept represents. That is, for example, the mental concept of the relation left of comprises the different ways of perceiving the relation left of such as certain eye movements, hand movements, attending to certain sound patterns, and hearing the words “left of” in a sentence. The so-defined mental concepts of PIT differ from symbols as often used in cognitive science and artificial intelligence (for example, ACT-R (Anderson et al., 2004), physical symbol system (Newell, 1990), or mentalese (Fodor, 1975)), because 1) they do not contain the semantics of the entity they represent, and 2) they do not directly reflect properties of the entity they represent. The semantics of a mental concept, that is, what the mental concept means to the organism, corresponds not to the processing or the activation of the mental concept, but the semantics are manifested in the process of executing the linked perception actions. That is, the semantics of an entity are the perception of that entity, i.e., what seeing, touching, or otherwise perceiving the entity is like. The mental concepts also do not directly reflect the properties of the represented entity. Consider, for example, that a depictive mental representation of an entity does preserve and thus reflect properties of the represented entity (e.g., Kosslyn, 1994). The properties of an entity instead become available by the perceptual feedback of the perceptual actions in visual perception. In mental imagery, as it will be discussed later, the employment of the linked perceptual action generates a perceptual instance of the represented entity which makes some of the properties of the entity available.

* sít konceptů, priming ,relevance

A set of mental concepts describing a scene incorporates the input of all modalities. That is, the perception of, for example, a cheese contains not only the visual and spatial information of it conveyed via visual perception but also the smell that was perceived and its texture and feel when it was touched. The resulting mental concepts of the perception through the different modalities are combined in one final conceptual description of that cheese. Importantly, also subtle and fully subconscious information such as that communicated via different demand or task characteristics (Orne, 1962) is assumed to be included in the final conceptual description. The different modalities can also give conflicting input as in, for example, the McGurk effect (McGurk & MacDonald, 1976). The McGurk effect is an example of sensory integration. When seeing a video of someone saying “ga” without sound but at the same time hearing the sound “ba”, we perceive the person in the video actually saying “da” which is a mixture of those two sounds. Conflicting mental concepts can be part of the conceptual description of a scene. When this conceptual description is processed during the mental imagination of the scene, these conflicting mental concepts might be integrated to make the mental image of the scene consistent.

The process of mental imagery starts with a conceptual description of what is to be imagined. That is, mental imagery starts with the end product of visual perception. A conceptual description of a scene consists of a set of mental concepts such as house, left of, tree. As discussed in Section 3.1.5 mental concepts consist of links to those perceptual actions which are used to identify the mental concepts, i.e., they are used to look at that thing which the respective mental concept represents. In mental imagery these links from mental concepts to perceptual actions are used to create an instance of perceptual information that corresponds to the respective set of mental concepts. The mental concepts are successively mapped onto perceptual actions which are then executed either overtly, e.g., spontaneous eye movements, or covertly. The execution yields perceptual information, for example, information about the change of gaze position. This process of picking and employing perceptual actions for a given mental concept in order to retrieve perceptual information is referred to as instantiation. The term instantiation is used because the perceptual information which is made available by the employment of perceptual actions represents one (perceptual) instance of the mental concepts that conceptually describe the mental image. The perceptual information made available through instantiation is mapped onto mental concepts by the VS-LTM just as it is the case in visual perception. The perceptual information and the mental concepts that have been identified based on it, influence the instantiation of further mental concepts. Again, similar to visual perception, from all identified mental concepts and their respective perceptual information, an interpretation is drawn and held in short-term memory. The interpretation is the most plausible subset of all identified mental concepts with their perceptual information. This interpretation in short-term memory constitutes the mental image. The perceptual information of the mental image held in short-term memory can be used for further processing, e.g., inferring new information such as previously not identified spatial relations.[/i]

Tak se identifikuje kontrast,tvar, barva.. postupně se dostaneme z identifikací až k tomu že je to strom, je to jehličnan , smrk tak že výsledkem budou koncepty z různou úrovní abstrakce.

Tak se identifikuje kontrast,tvar, barva.. postupně se dostaneme z identifikací až k tomu že je to strom, je to jehličnan , smrk tak že výsledkem budou koncepty z různou úrovní abstrakce.